This week’s Forgotten Friday looks at the history of Shell Shock during the First World War to help raise awareness of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in time for National PTSD Awareness Day on the 27th June 2022.

What was Shell Shock?

The First World War ended with the surrender of Germany on the 11th November 1918, however for soldiers returning home physically wounded and psychologically traumatised, the pain of war did not end with the armistice. After witnessing unimaginable horrors of war, many soldiers suffered from what contemporaries called ‘Shell Shock’. The name derives from contemporary notions that repetitive shelling was a primary cause of the condition.

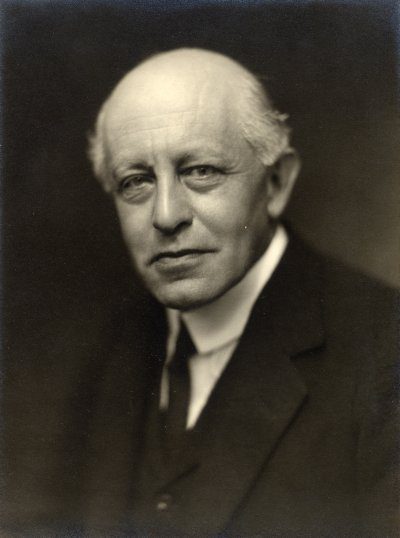

Shell shock is a term coined during the First World War by British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers, to describe the type of post-traumatic stress disorder many soldiers suffered from during the war. Shell shock was an umbrella term used to describe symptoms ranging from paralysis, amnesia and loss of taste and smell after psychological trauma induced by the violence of warfare. The root cause of this type of psychological response is unknown and is experienced by veterans to this day, now recognised as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD.

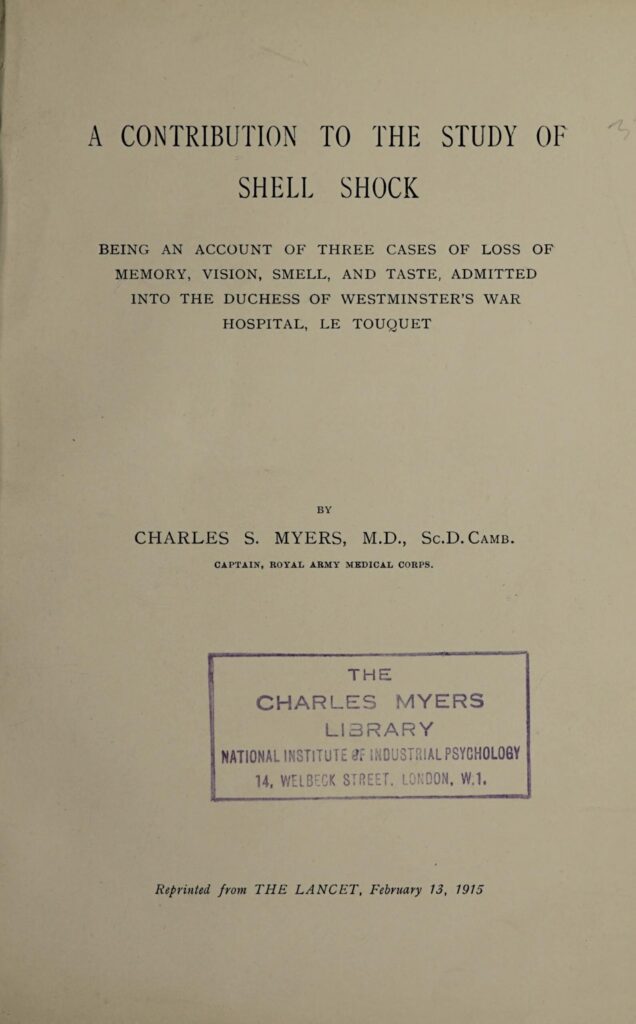

Charles Samuel Myers (1973-1946) was an English physician, director of the Cambridge Psychological Laboratory, and the first person to publish the term ‘shell shock’ in medical literature. Myers worked as a volunteer doctor at the Duchess of Westminster’s War Hospital at Le Touquet, France, where he observed many patients suffering from shell shock. He published his findings in The Lancet, under the title ‘A contribution to the study of shell shock-study of three cases of loss of memory, vision, smell, and taste’ (1915). His work focused on the effects of shell shock on sensory functions and memory on three patients in France and proposed that shell shock was induced through head trauma. Other symptoms included loss of the ability to speak, tremors and fatigue. He concluded that the patients were not faking their illnesses, however he could neither find physical injuries to support their symptoms. He therefore argued that their symptoms were a result of suppressed psychological trauma.

Contemporary treatments of shell shock

The effects of shell shock became a growing concern during the war as increasing numbers of front-line troops suffered from a debilitating illness that army medics did not understand and thus struggled to treat.

Myers believed that men could be treated through cognitive reintegration which focused upon cognitive and behavioural symptoms of shell shock. This required transporting effected men to special units away from the front-line, removing them from the sounds of war to recover. By December 1916, following Myer’s advice, the British Army had set up four units of this kind. His approach to treatment required individual attention and so he also requested that the War Office establish training courses to cater to higher staff to patient ratios. Other treatments involved electroshock therapy which aimed to alleviate physical symptoms however it was typically ineffective. Not everyone agreed with Myer’s assessment, and many believed that shell shock was a result of weakmindedness and a feeble attempt to skirt military duties. This led to a significant number of soldiers being charged by court martial for cowardice and executed despite being diagnosed with shell shock.

PTSD Today

Although shell shock shares similar features with PTSD, approaches to the treatment and conceptualisation of psychological trauma have evolved drastically since the beginning of the 20th century. PTSD can now be successfully treated with the aid of antidepressants such as paroxetine or sertraline or through psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR).

Despite advancements to our understanding and treatment of the condition, PTSD is still a serious and debilitating condition which affects 1 in every 3 people who have a traumatic experience (not only from involvement in warfare).

To find out more about PTSD and ways to manage the condition or support loved ones, click here.