In today’s #ForgottenFriday, we are looking into the story of the Tunneller’s Trolley; how did they try to escape and was it successful?

Perhaps the two best-known escapes by prisoners of war during the Second World War were from Stalag Luft III. The camp was in Sagan, in Silesia: then part of Germany, and now part of Poland. The camp, at its biggest, held 10,000 prisoners and covered over 59 acres with 8 kilometres (5 miles) of perimeter fencing. The prisoners at Stalag Luft III included Fleet Arm aircrew and USAAF, plus a few non-aircrew soldiers (the reason for this exception is not easy to establish).

The site was selected for two reasons. First it was in the middle of occupied Europe and therefore any escaper would have to travel a very long distance to reach a neutral country: Sweden, Spain, and Switzerland being the closest. Second, the sandy soil made tunnelling difficult because it caved in so easily, and the yellow subsoil stood out clearly against the grey surface dust. It could not be dumped just anywhere without being seen by the camp guards. Furthermore, the sand could easily be spotted on the prisoners’ clothing giving it away that a tunnel had been dug somewhere.

Similarly, the design of the camp also hindered tunnelling. The prisoner accommodation huts were raised two feet above the ground making any tunnelling from prisoner accommodation obvious. Finally, a seismograph microphone was placed under each hut around the perimeters of the camp to detect the sound of digging.

The first successful escape was in October 1943 using a wooden gym vaulting horse as a cover for the digging. The vibration caused by men running, jumping, and landing prevented the microphones from detecting the sounds of digging. The ‘horse’ was positioned quite near the perimeter wire, reducing the length the tunnel had to be.

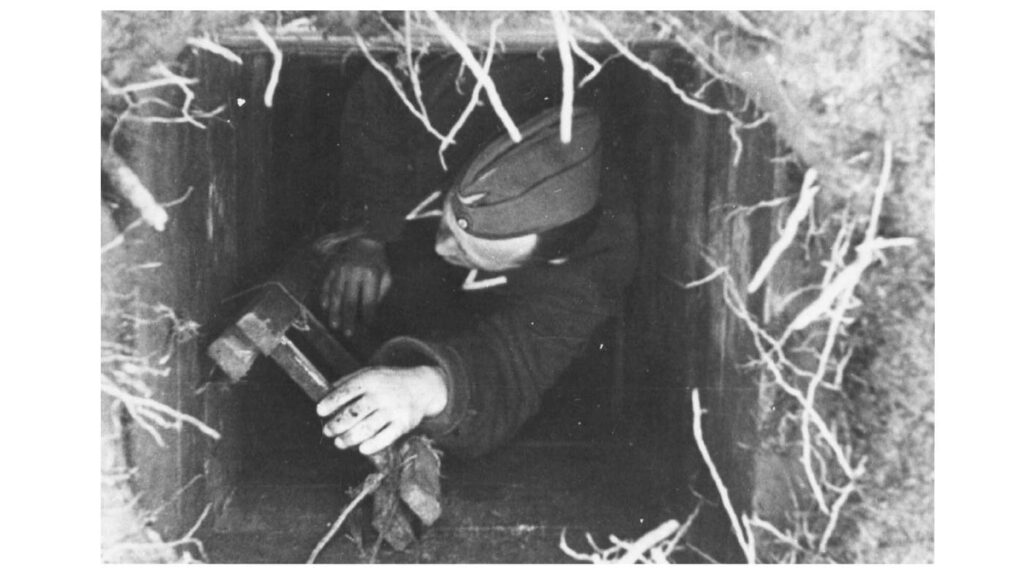

The next partially successful escape was conceived by Squadron Leader Roger Bushell RAF in the Spring of 1943, well known as the Great Escape. He planned to dig three big tunnels, named Tom, Dick, and Harry. He believed that if one tunnel was found, the Germans would have assumed that there were no others. He aimed to get more than 200 POWs out. To avoid the problem caused by the raised accommodation huts, Tom’s and Harry’s entrances were each dug under a camp stove through the cement and concrete plinth, which extended all the way from the hut floor to the ground. This was a difficult job taking hours of work with a pick. The tunnels were 30 feet below the surface to avoid the digging sounds being picked up by the microphones.

A wooden railway was built along each tunnel. Small wooden trucks or trolleys wee pulled along by rope from haulage points positioned at intervals along the tunnel. A ventilation system of empty dried milk tins stuck end to end was laid under the tunnel floor with bellows pumps made from kitbags.

Dick was abandoned when the area planned for the tunnel exit was cleared of trees for a new building. It was thereafter used to dump sand from the other two tunnels, to store the large quantity of escape clothing, false papers and equipment stolen from the Germans.

Tom was discovered in the Summer of 1943, so all efforts were concentrated on Harry, which was finished in March 1944, Harry ended up being 336 feet long. This unfortunately was not enough; it did not, as planned, reach the trees some yards beyond the wire: as the escapers would discover.

The breakout occurred on the night of 24th March 1944. 76 men got out, before a guard spotted a man lying by the tunnel exit, which was well short of the trees. Three escapers reached safely, 50 were murdered by the Gestapo, and 17 were returned to Sagan, four to Sachsenhausen and two to Colditz.

You can see a recreation of the wooden tunnel and ventilation system at our museum in Hut 28. Watch out for the guard dog though!