This week’s #ForgottenFriday looks at the life of POW before and after the Geneva Convention

The 27th July marked 93 years since the Geneva Convention on prisoners of war (POWs) was signed at Geneva, Switzerland.

The convention aimed to codify the status and respected treatment of POWs and laid down rules on the conditions in which prisoners should be captured and interned, including hygiene standards, mental and physical provisions, and the general organisation of camps. Camps during the Second World War were measured against these regulations to ensure the humane treatment of camps’ inhabitants. However, the tradition of capturing enemy peoples as spoils of warfare has a long history, so how has the status of POWs evolved and what were the experiences of POWs throughout time?

POWs during Ancient times

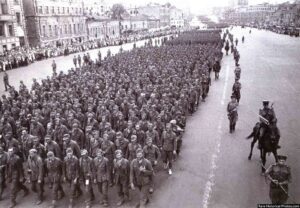

Within Ancient civilisations, prisoners of war were considered the victor’s property and could be sold into slavery or slaughtered amass if this wasn’t a viable option. There were no universal codes of conduct relating to the treatment of POWs so if captured, a person’s future was unpredictable and surrender most likely resulted in either their freedom or life being taken. POWs were used to display military superiority; for example, within the Roman Empire, captives were often paraded through the capital during Triumphs. These were civil ceremonies that celebrated the success of a military commander after a campaign and POWs were used as spectacles of victory. This practice was emulated during the Second World War when Soviet troops marched German prisoners through the centre of Moscow on the 17th July 1945.

Yinxu Sacrificial Burial Site

Human sacrifice has a long history and ancient cultures such as the Ancient Greeks, the Aztecs, Incas and in Ancient China sometimes offered captives for ritual sacrifices. Sacrificial pits are common throughout the Shang capital of Yinxu dating from the Shang dynasty (16th century BC to the 11th century BC). Bioarchaeologists have estimated that over the course of about 200 years, more than 13,000 captives were sacrificed in Yinxu, usually males ages 15 to 35. Isotopic analysis on bones found at the site support the theory that captives of war were kept (most likely as labourers) before being sacrificed after some years.

Changing status of POWs

A major shift in the status of prisoners of war came during the mid-17th century. Emer de Vattel, a renowned Swiss lawyer proposed the revolutionary notion that from the moment the enemy surrenders, they should not be harmed. Within his work titled Laws of Nations (1758) he states ‘(a)s soon as your enemy has laid down his arms and surrendered his body, you no longer have any right over his life’. Another change that happened was that the treatment of POWs became the responsibility of the state, not of the individual captor and thus international frameworks of conduct were slowly established. An example of the this can be seen through the Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1785) signed between Prussia and the United States which shows premediated efforts to regulate the treatment of POWs prior to the outbreak of war.

Emer de Vattel, 1714-1767

POWs in Britain

Prisoners of war were first interned in Britain during the Napoleonic wars and Norman Cross Prison in Peterborough is an example of the first purpose-built POW camp in the country! Following from this, prisoners were interned in hundreds of locations across England during the First World War. The 1907 Hague Convention relating to the laws and customs of war on land outlined the treatment of POWs in line with their rank and they received board, lodging and clothing comparable to that of their captors. Some contemporaries even complained about the level of luxury some prisoners enjoyed which is very different compared to the treatment of captive people in the ancient world. For example, at the officer’s camp at Donington Hall in North West Leicestershire, officers had a choice of dishes, wine lists and received a cash allowance sent directly from Germany each week.

Donington Hall – Officer’s POW camp

Donington Hall POW Common Room

The 1929 Geneva Convention

There were still flaws in the Hague Convention and reflecting on what was learnt during the First World War, the International Committee of the Red Cross drew up a draft convention which was submitted to the Diplomatic Conference convened at Geneva in 1929. The Convention did not replace but added to the provisions of the Hague regulations. The most important innovations related to the organisation of prisoners’ work and the control exercised by protecting powers. The 1929 Convention was replaced by the third Geneva Convention on 12th August 1949 and is no longer in operation.

German Prisoners Parade, Moscow

To find out more about the experiences of POWs during the Second World War, head over to hut 10 at Eden Camp which will tell you everything you need to know about the experiences of captives in Malton and beyond!