With the start of the Second World War came Operation Pied Piper.

This was the plan to evacuate civilians from cities and other areas that were at high risk of being bombed or becoming a battlefield in the event of an invasion.

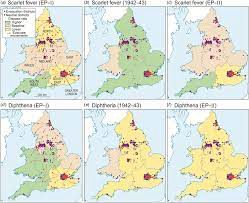

The country was split into three types of areas: Evacuation, Neutral and Reception, with the first Evacuation areas including places like Greater London, Birmingham and Glasgow, and Reception areas being rural such as Kent, East Anglia, and Wales. Neutral areas were places that would neither send nor receive evacuees.

Evacuees themselves were split into four categories, focused on specific social groups deemed non-essential to war work:

1) school-age children

2) the infirm

3) pregnant women

4) mothers with babies or pre-school children (who would be evacuated together).

Three days before the war broke out on the morning of 31st August 1939, an order of evacuation was given for the next day. Children began to assemble their belongings and meet at their schools on the morning of 1st September, and Operation Pied Piper commenced.

Over the country, many volunteers helped to take in evacuees following the order of Pied Piper. London alone had 1,589 assembly points and although most children boarded evacuation trains at their local stations, trains ran out of the capital main stations every nine minutes for nine hours. Some children in London were even evacuated by ship from the river Thames, sailing to ports such as Great Yarmouth, Felixstowe and Lowestoft. The process involved teachers, local authority officials, railway staff and members of the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS), who provided practical assistance, looking after tired evacuees at stations and providing refreshments.

Over the course of the first three days of official evacuation 1.5 million people were moved from cities to the countryside. In England alone 673,000 unaccompanied schoolchildren, 406,000 mothers and young children and 3,000 expectant mothers were relocated. Children had to carry a kit, and a Ministry of Health leaflet outlined what this should comprise: ‘a handbag or case containing the child’s gas mask, a change of under-clothing, night clothes, house shoes or plimsolls, spare stockings or socks, a toothbrush, a comb, towel, soap and face cloth, handkerchiefs; and, if possible, a warm coat or mackintosh. Each child should bring a packet of food for the day.’ Each child had a luggage label pinned to their coat on which was written their name, school and evacuation authority. Separated from their parents, and, sometimes, siblings, schoolchildren were instead accompanied on their journey by a small army of guardians, mostly teachers and WVS personnel.

Evacuation day was inevitably a deeply emotional and traumatic experience for all involved and full of uncertainty and tearful goodbyes. Although some children were excited at the prospect of the forthcoming ‘adventure’, most evacuees were unaware of where they were going, what they would be doing and when they would be coming back. Faced with upheaval and lasting separation from loved ones, the initial separation was devastating and heart-rending for both mothers and children as whole families were dislocated and uprooted. However, the fear of bombing attacks meant that most parents considered evacuation for the best, as children would be safer away from the city.

It was one thing to remove children from areas which were at risk, but it was another to find somewhere for them to go. Various options were discussed, with civilians generally preferring the option of camps to be set up and supervised by teachers, but government ministers instead decided to use private billets. It became compulsory for homes to host assigned evacuees, with host families being paid 10 shillings and sixpence (53p; equivalent to £26 today) for the first unaccompanied child, and 8 shillings and sixpence for any subsequent children. Places were assessed in terms of accommodation available rather than suitability or the hosts’ inclination for raising children. This could lead to resentment of those who would be forced to care for children against their will, compounded with that many children did not want to be there in the first place and tried to run away. This problem was particularly prevalent in the lower-class families, as wealthier families often had relatives or school friends in the country to take in their children, rather than relying on strangers to look after the children.

Do you have any stories of being an evacuee or know someone who was an evacuee? Please let us know!

Email Summer, our Collections & Engagement Manager – we would love to add the stories for our digital archive!

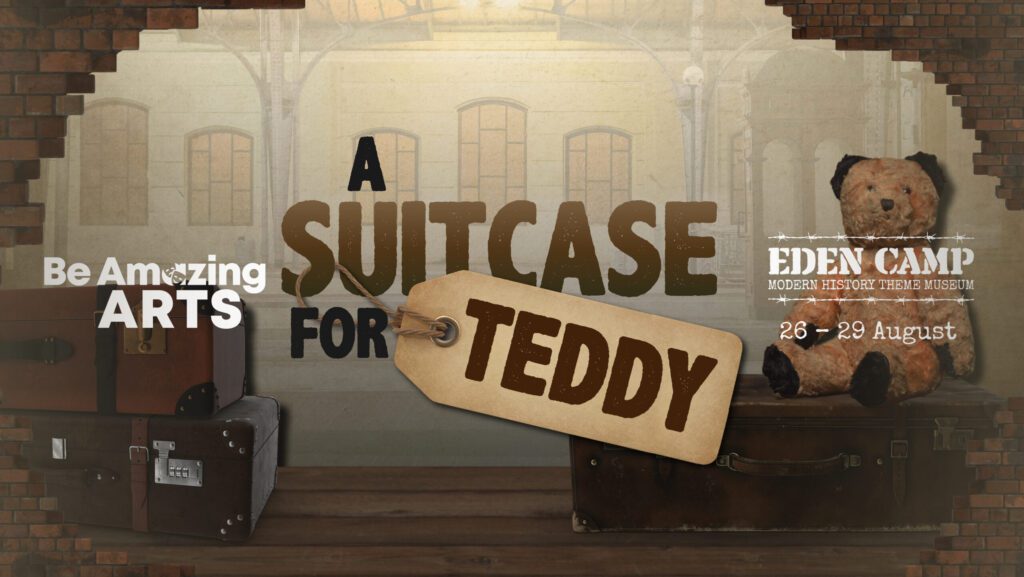

This Summer, stand in the shoes of an evacuee with a brand new immersive promenade theatre performance brought to you by Be Amazing Arts!

We follow the journey of a group of children from a small school house in Guernsey who find themselves in ‘God’s Own Country’; from the announcement that they would be going to the mainland to stay to escape Nazi Occupation, the different journeys that brought them into Yorkshire to adapting to their new lives in such uncertain times.

In the present day, where we are seeing so many refugees displaced, leaving everything they know behind to escape danger, this show reminds us that throughout history human kind has shown compassion and open arms to those in immediate danger and in need. We will rally, we will fight and we will prevail!

Why not make a day of it? Book your Suitcase tickets now and receive 10% off museum admission for the same day as your performance! Click the image below!